The Grossman Ensemble has been premiering works by innovative composers since their inception in 2018, but it is rare that these composers are members of the ensemble itself. Greg Beyer bridges this gap. As both a composer and a percussionist in the Grossman Ensemble, Beyer's unique position offers him special insight into the process behind composing for this group.

We interviewed Beyer about his experience performing in and composing for the Grossman Ensemble, his forthcoming numerically-inspired work (Amen)ding Thirteen: A Sign of Abundance, dancing, the berimbau, and everything in between. Read on to learn more.

As you’ve written previously, the number 13 has a strong cultural hold as both a negative and positive symbol. In what ways does the number 13 culturally, or philosophically, inform your work (Amen)ding Thirteen: A Sign of Abundance?

The journey of writing a work for the Grossman Ensemble began with a simple question that emerged when staring at a blank page of manuscript paper… ”Where to begin writing for this unique ensemble of thirteen fantastic musicians?” In the physical act of writing that question on the page, the word “thirteen” gradually took hold as an animating force guiding the work’s development.

In the United States and elsewhere in the west, the ancient superstition swirling around the number thirteen is such a powerful cultural phenomenon that we have a word for it, “trikaidekaphobia,” the fear of thirteen. And although it is completely irrational, the phenomenon is so deeply seated in our culture that when I began traipsing across this subject in a presentation I offered the University of Chicago composition seminar two weeks ago, the room grew strangely quiet. Beyond the local and anecdotal, this phenomenon takes on proportions of national and global scale. According to the Otis Elevator Company, for every high rise in the United States with a named thirteenth floor, there are another six that skip from the twelfth to the fourteenth. And global financial statistics report losses in the millions of dollars annually on Friday the 13th out of a widespread fear of travel and other activities or negotiations involving an element of risk.

In other cultures thirteen carries no such negative charge, and in some cases it even represents the auspicious and perfectly natural. For example, Native American tribes referred to the North American continent as the “Great Turtle Island” and used the thirteen “scutes” (visibly embossed divisions) on a turtle’s shell as a physical symbol to follow the thirteen roughly 28-day cycles of their lunar calendar, something both deeply connected to living close to the earth (i.e. following its seasons of planting and of harvest, etc.) as well as something deeply feminine.

I am the Artistic Director of Arcomusical, a nonprofit ensemble dedicated to the Afro-Brazilian berimbau musical bow. And I play the berimbau in (Amen)ding Thirteen, as well as the Yoruban-Cuban batá, the Shona mbira dvavadzimu, and the drum set (an instrument of African-American creation). And as a percussionist with an enormous debt of gratitude for African musical cultures throughout the Americas, I took some joy in considering that the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was the first of the Reconstruction Amendments and it abolished slavery in the land. However, thanks to recent scholarship by Isabel Wilkerson, Ava DuVernay, and so many others, we know full well that life in a post-Thirteenth America has been rife with over a century full of backlash against our African-American brothers and sisters. All too often, irrational fear begets deadly violence.

And so, in Wilkersonian fashion, (Amen)ding Thirteen is a musical prayer offering that we may still find a better way forward for everyone.

In what ways does the number 13 structurally inform your composition?

Beginning with the number of musicians in the Grossman Ensemble, I quickly built a list of thirteen-centric possible musical connections to write the piece. Specifically, I considered:

thirteen musicians…thirteen harmonies…thirteenth chords…palindromic 13/8 meter (3+2+3+2+3)…thirteen rhythmic variations…a thirteen-minute piece with five formal sections of 3+2+3+2+3 minutes…tempi in multiples of thirteen…and the sacred rhythms of Babalú Ayé, the Afro-Cuban orisha (deity) of sickness and of healing, whose numerological symbol is thirteen…

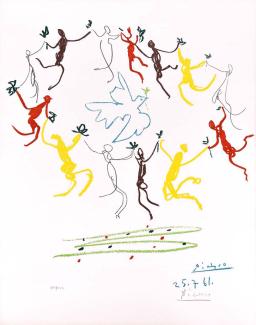

You wrote that Picasso’s 1961 drawing Ronde de la jeunesse, which features 13 dancers, also served as inspiration for your work. How is dancing emulated in (Amen)ding Thirteen?

Shortly after completing the first draft of the work for submission on December 6th, 2023, I attended a holiday party in Denton, Texas with my wife, and was introduced to Picasso’s charming July 7th, 1961 painting, “Ronde de la jeunesse.” Having already composed an element of dance directly into the piece at its midpoint (come to the concert to learn more!), I was shocked to discover that Picasso depicted thirteen young dancers circling and swaying around a blue dove - a secular symbol for peace, yet with ancient connections to early Christianity. The colors of the 13 dancers - 3 black, 3 red, 3 yellow, and 4 white - immediately brought to mind the powerful lyrics of Stevie Wonder’s 1976 anthem, “Black Man.” And below the central image is another series of thirteen red and black dots scattered around a shape that could easily be interpreted as the number 3. And then I thought…the centrally located dove and its Holy Trinity symbolism conveys a story of three-in-one and one-in-three…

3+1…

1+3…

13…

As Picasso’s youthful and childlike dance implies, and in Wonderian and Wilkersonian fashion, (Amen)ding Thirteen is not only a musical prayer offering, it is an invitation to dance in thirteen like its never been danced. In my opinion, dance may be one of the most powerful tools we have to break the feverish nonsense of unfounded fear that holds us back from our best selves and may allow us to pierce darkness into the light of a better tomorrow for everyone.

How has your experience as a member of the Grossman Ensemble altered your compositional approach? For example, did you find yourself composing generally for each instrument, or did you cater each part to the strengths and personalities of the individual members?

Profoundly, yes, and YES!

I am so grateful to be a member of the Grossman Ensemble and to have had this opportunity to think about my colleagues and their incredible individual and collective artistry on a near daily basis over these past several months. As we’ve been performing together since 2018, I have come to know powerful moments of joy and beauty in the best moments of our repertoire, and I have seen first-hand the sorts of musical ideas that animate and enliven my colleagues, some of whom I’ve known for decades.

I knew, for example, that I could write a jazz-inspired section of improvisation for saxophonist Taimur Sullivan and myself, trusting that the result would be like nothing the ensemble has yet performed. And I referred specifically to the low-voice textures of David Rakowski’s 2018 work for the Grossman Ensemble, “Lee,” dedicated to and inspired by composer and pianist Lee Hyla (1952-2014). After the first rehearsal, I was knocked out when Taimur approached me and said, “Man, thanks for the great piece. We haven’t had low voice writing like that since we played Rakowski’s “Lee!” And I exclaimed, “You got it! That was exactly the inspiration!”

And other repertoire found its way into my composition, too. Before I wrote a note of my own, I studied the fantastic scores to Shulamit Ran’s “Grand Rounds” and David Dzubay’s “PHO” measure by measure, sitting at a piano and working out all of their meticulous detail. At our first Wild Card Concert back in the fall of 2022, we played George Benjamin’s incredible “At First Light.” The profound, breathtaking beauty of the opening of the third movement of that work was deeply magical for me when I was studying the score, and that moment became the model for the slowest moving portion of my work.

Your previous compositions are written primarily for percussion instruments. What was it like to compose for the Grossman Ensemble’s unique grouping of instruments?

At first it was daunting, but before long it became liberating, playful, and a joyful practice of discovery. And what I have found incredibly helpful is the unique workshopping process that the Grossman Ensemble embraces. For example, after our first rehearsal with the first draft of the work, pianist and composer Daniel Pesca called me over and said, “Hey, fun piano part! Let me show you a few ideas I had while playing through the notes!” And then he proceeded to shred! He demonstrated multi-voice textures that literally left me agape in awe. I said, “Oh dear, I’ve given you a marimba part to play, haven’t I? And you are an incredible pianist!” I video taped Daniel’s examples and sat at the piano myself between the first and second rehearsals in order to reconsider the piano part from a more hands-on and tactile perspective. And it changed EVERYTHING. Daniel, thank you for both the composition and the piano lesson!

On the flip side, it has been a joy to bring elements of percussion writing to my colleagues. When I introduce the berimbau shortly after the arrival of the final section of the work in 13/8 meter, I give my string and harp colleagues berimbau-esque lines to play with me in harmony. When Doyle (viola) turned to me at his entrance and smiled as we began playing in rhythmic unison, I just about lost it with joyful emotion. This is such a good group!

And when the ensemble begins intoning the sacred batá rhythms of Babalu-Ayé whose numerological symbol is 13, I’ve asked John (percussion) and Katie (clarinet) to join me in playing the trio of batá drums. And precisely at that moment I have given Connie (flute) and Matt (horn) low and high sleigh bells to play to invoke the sound of the iyá drum’s chaworó and chaworí.

What has been your most memorable moment from your time with the Grossman Ensemble?

We have had some stunning performances, and some of the many excellent and memorable works I’ve already mentioned (Rakowski, Ran, Dzubay, Benjamin). And here is a short list of other incredible works we’ve been fortunate enough to play:

Eric Nathan’s “In Between”

Augusta Read Thomas’s “Terpsichore’s Box of Dreams”

Keith Fitch’s “Still”

Aaron Travers’s “The Nameless Path”

Frédéric Durieux’s “Theater of Shadows”

Amy Williams’s “Telephone”

And I feel that the ensemble is becoming more joyful and capable by the cycle. At the beginning of this year, for example, we worked with Sean Shepherd and a host of 18 incredible musicians from around the world to rehearse and record his epic “Concerto for Ensemble.” In those rehearsals, surrounded by unflinchingly professional master musicians, I thought to myself, “This ensemble is capable of anything. We are an unstoppable force.”

When you’re not composing or performing, what do you like to do in your free time?

Simple things that provide some calm and intimacy in an otherwise busy life. I love spending time with my wife, Daphne, walking our dogs, making meals together, taking care of our yard and garden, reading stories together. Physical fitness is also important to me. I am the NIU Capoeira Club Faculty Advisor. The club meets weekly for capoeira training, and I make a point of getting to the gym a few times a week.

What’s next for you?

Arcomusical has been working for the past two years on a very special project we are calling Berimbatá. It is my arrangement for Arcomusical’s unique tuned berimbau ensemble of the Afro-Cuban Lucumí oro seco batá drumming liturgy that offers a musical salutation to a series of twenty-two sacred beings known as orishas/orixás. The synergy embedded in this project is the reason both the batá and the berimbau show up in (Amen)ding Thirteen. Arcomusical has performed this music on both batá and on berimbau in public venues and in university percussion classes for the past several months, and Berimbatá will be the focus of the next Arcomusical album, which we intend to record this coming May 2024.