Image courtesy of UChicago Arts.

Logan Center’s MAPS OF FORM features visual depictions of musical works by students and faculty

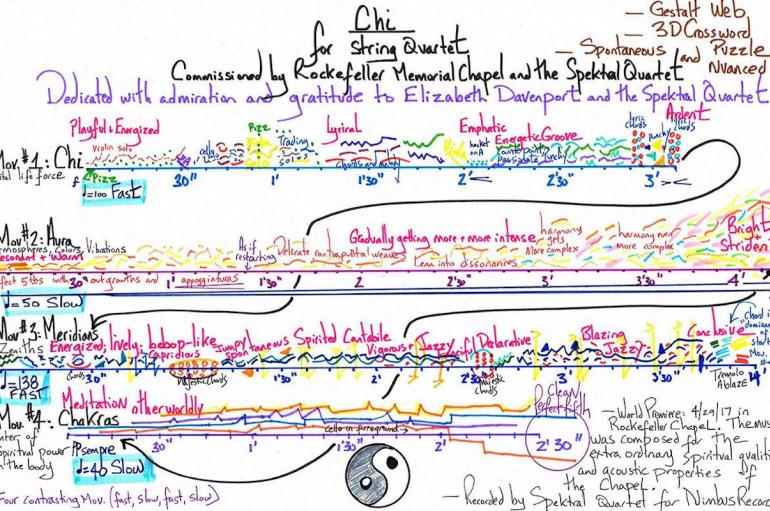

For composers, drawing a “map” of music can give shape to a new work and articulate its overarching ideas. As evocations of the composer’s intentions—from sweeping curves to stars, birds and brightly-colored dots—such maps capture the ebbs and flows within a musical piece and complement musical scores, serving as guides for performers.

MAPS OF FORM, a new exhibition at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, presents a collection of these musical illustrations as works of art in their own right. Drawn by UChicago faculty and graduate composition students, the maps vary from abstract representations of operatic arias in numbers and letters to contemporary works illustrated with chariots and drawings of hanging mobiles.

The maps of form—as well as videos of composers describing them and performances of some of the featured compositions—are included in the online virtual exhibition. To see all of the compositions and videos, viewers can expand the slide deck to full screen and click through the gallery as if they were present in the Logan Café, where the physical version of the exhibition is open to UChicago students, staff and faculty with proper COVID-19 safety precautions.

Conceived by Leigh Fagin, the Logan Center’s senior director of programming and engagement, the exhibition was inspired in part by the work of Prof. Augusta Read Thomas, a renowned contemporary composer.

Thomas said her creative process takes many forms—from improvising on the piano to dancing, physicalizing her rhythmic contrapuntal lines and singing in her apartment. Her drawings are one step in that process: sketches on the way to a finished product.

“Drawing chords, harmonic rhythms, progressions, tempos and maps of what I’m building is a way of holding onto ideas as they bubble up, so they don’t evaporate into thin air,” said Thomas, the University Professor of Composition.

Kari Watson, a first-year Ph.D. student in the music department, agreed that drawing a map of form is a valuable step in her pre-composition process.

“I see the map as a sort of broad-stroke score that lays out the ‘vital DNA’ in a piece,” Watson said. “It allows you to test the formal arguments in a gestural way, without getting stuck in the nitty-gritty details right from the start.”

Watson’s map illustrates the seven movements of her percussion piece Mx.Mechanica. The piece explores the drum set as a metaphorical machine activated by the drummer: Over the course of seven musical “scenes,” it revs up, goes full throttle and “collapses” into a pile of junk. To craft it, Watson drew upon the BBC’s sound archive, which includes a collection of sounds from defunct technology that are not a part of the modern soundscape.

“I’m interested in the idea of planned obsolescence,” Watson said. “And listening to these sounds—like a windmill and a sound from an old rug factory—made me think about how they harkened back to a different world.”

Fellow first-year Ph.D. student Paul Novak took a different approach to illustrate his composition, titled a string quartet is like a flock of birds. Novak’s piece was commissioned by the Kinetic Ensemble, a Houston-based conductorless string orchestra, for its first concert since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic on November 1, 2020.

“The piece is structured in nine meditations and dances, alternating between somber, reflective music and a fast, animated celebrations,” Novak said. “I wanted it to capture the joyful spirit of coming together and making music again after a long period of isolation.” In Novak’s map, the instruments start out in their own separate worlds, but eventually unite.

Maps by other composers demonstrate a variety of different interpretations of the motif. Andrew Stock, a second-year Ph.D. student, said his map of form is both a window into his creative process and an analysis of his composition, titled from Fidelio: Gott! welch Dunkel hier (“God! What darkness here”).

To produce his map of form, Stock took an aria from a prison scene in Beethoven’s opera Fidelio and put it into a kind of grid, leaving out all the information about pitches and rhythms and replacing it with black text of the lyrics and red numbers symbolizing the musical events that happen in each measure of the voice part of the aria—six notes, for example, are a numeral 6.

Stock said his goal, in part, was to deliberately misappropriate one of the classical repertoire's most archetypal prison arias as a kind of critique or commentary.

“I’m very interested in grid forms, and in abstracting source material. To me, those are modernist devices,” he said.

Stock added that he chose a classic ‘prison aria’ in part to connect notions about the grid, European history, and the dehumanizing effects of carceral space.

Asst. Prof. Sam Pluta, an electronic musician, drew a map that is reminiscent of the branching patterns in a tree of life diagram. The map gives insight into a unique instrument and compositional modality that Pluta developed himself.

Pluta’s instrument consists of software and a joystick like those used in some video games. The joystick interfaces with a “multidimensional software synthesizer” that employs a system of code to create sounds.

What exactly does that mean? Pluta says it’s helpful to think about his map of form as illustrating not a traditional, linear piece of music but a system of interaction that results in a complex set of possibilities, like a character exploring the landscape of a video game.

“I’ve created a sonic system that is too vast and complex to map directly in its entirety,” Pluta said. “But the cool thing about the neural network is that I can map it to any small region of that sonic space, if I just train it to a different set of parameters.”

Taken together, the maps and commentary by composers offer a rare glimpse into their studios, pulling back the curtain on how music moves from an idea, onto a page and out to an audience through performances. The exhibition can be visited virtually online and in person through the end of winter quarter.

This story was originally published here on UChicago News.